FEATURED

What Is Red Mercury – Where To Buy Online Safe

What Is Red Mercury?

Hoax or real?

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/GettyImages-1160193137-38aaa94678424e84a295daec813788bb.jpg)

The science newsgroups have been abuzz with tales of a 2-kiloton yield Russian red mercury fusion device, theoretically in the possession of terrorists. This, of course, prompts the question: What is red mercury? The answer to this question depends largely on who you ask. Is red mercury real? Absolutely, but definitions vary. Cinnabar/vermillion is the most common answer. However, the Russian tritium fusion bomb is more interesting.

What Is Red Mercury?

- Cinnabar/Vermillion

Cinnabar is naturally occurring mercuric sulfide (HgS), while vermillion is the name given to the red pigment derived from either natural or manufactured cinnabar. - Mercury (II) IodideThe alpha crystalline form of mercury (II) iodide is called red mercury, which changes to the yellow beta form at 127 C.

- Any Red-Colored Mercury Compound Originating in Russia

Red can also be used in the Cold War definition of red, meaning communist. It is doubtful that anyone today is using red mercury in this manner, but it’s a possible interpretation. - A Ballotechnic Mercury Compound Presumably Red in Color

Ballotechnics are substances that react very energetically in response to high-pressure shock compression. Google’s Sci.Chem group has had a lively ongoing discussion about the possibility of an explosive form of mercury antimony oxide.

According to some reports, red mercury is a cherry-red semi-liquid that is produced by irradiating elemental mercury with mercury antimony oxide in a Russian nuclear reactor. Some people think that red mercury is so explosive that it can be used to trigger a fusion reaction in tritium or a deuterium-tritium mixture. Pure fusion devices don’t require fissionable material, so it’s easier to get the materials needed to make one and easier to transport said materials from one place to another.

Other reports refer to a documentary in which it was possible to read a report on Hg2Sb207, in which the compound had a density of 20.20 Kg/dm3. It is plausible that mercury antimony oxide, as a low-density powder, may be of interest as a ballotechnic material. The high-density material seems unlikely. It would also seem unreasonably dangerous (to the maker) to use a ballotechnic material in a fusion device. One intriguing source mentions a liquid explosive, HgSbO, made by DuPont laboratories and listed in the international chemical register as number 20720-76-7. - A Military Code Name for a New Nuclear Material

This definition originates from the extraordinarily high prices commanded and paid for a substance called red mercury that was manufactured in Russia. The price ($200,000-$300,000 per kilogram) and trade restrictions were consistent with a nuclear material as opposed to cinnabar.

‘Red mercury’: Why does this strange myth persist?

- Published

For centuries rumours have persisted about a powerful and mysterious substance. And these days, adverts and videos offering it for sale can be found online. Why has the story of “red mercury” endured?

Some people believe it’s a magical healing elixir found buried in the mouths of ancient Egyptian mummies.

Or could it be a powerful nuclear material that might bring about the apocalypse?

Videos on YouTube extol its vampire-like properties. Others claim it can be found in vintage sewing machines or in the nests of bats.

There’s one small problem with these tales – the substance doesn’t actually exist. Red mercury is a red herring.

The hunt for red mercury

Despite this, you can find it being hawked on social media and on numerous websites. Tiny amounts are sometimes priced at thousands of dollars.

Many of the adverts feature a blurry photo of a globule of red liquid on a dinner plate. Next to it there will often be a phone number scribbled on a piece of paper, for anybody foolish enough to want to contact the seller.

“Serious buyers only,” reads one advert. “We need proof of funds to make proof of product.”

The impression given is that a mysterious and illicit commodity is on offer.

“It’s a game of con artists and the danger is that people are going to be swindled, that they might be robbed or mugged, or that they’ll just waste their time,” says Lisa Wynn, head of the anthropology department at Macquarie University in Sydney.

Prof Wynn first came across the phenomenon when she was working at the pyramids of Giza in Egypt and sharing an office with the leading Egyptologist Dr Zahi Hawass.

One day Dr Hawass received a visit from a Saudi prince whose mother was in a coma.

“This man had been spending all of his energies and money trying to find something that would save his mother,” Prof Wynn recalls.

“So he turns to a sheikh in Saudi Arabia, a faith healer, who tells him there’s this magical substance that is found buried in the throats of mummies in ancient Egypt. And if you go to Egypt and ask this archaeologist, he will be able to provide you with red mercury.”

But when the man arrived in Egypt, the archaeologist set him straight.

“Dr Hawass says: ‘I’m so sorry about your mother, but this is bunk. There is no such thing as red mercury.'”

After witnessing this exchange, an astonished Prof Wynn discovered this was not a new experience for Dr Hawass and his colleagues. They often encountered Arabs who believed red mercury was a magic cure-all buried with the pharaohs.

It’s bats

The origins of this belief are hazy. Evidence of it can be found in the work of the medieval alchemist and philosopher Jabir ibn Hayyan, who wrote: “The most precious elixirs to ever have been blended on earth were hidden in the pyramids.”

In more recent times, some seeking red mercury have come to believe it can also be found in the nests of bats. Leave aside the inconvenient fact that bats do not actually build nests – this has not prevented fortune hunters from disturbing habitats to look for it.

Some have taken the bat theory one step further, and claim that red mercury comes from vampire bats. And so, the logic goes, the substance exhibits the same properties as horror movie vampires.

Evidence for this Dracula-in-liquid-form legend is offered in a number of bizarre YouTube videos, some of which have been viewed hundreds of thousands of times. Typically a red blob – that often looks suspiciously like it has been created using video graphics – is shown being repelled by garlic, and attracted by gold. When a mirror is placed beside it, the blob apparently has no reflection.

Red mercury’s supposedly amazing qualities don’t end there. It is alleged to have powers to summon jinns – Arabic for supernatural beings.

In 2009 a story spread in Saudi Arabia that red mercury could be procured without breaking into an ancient tomb or sifting through bat guano. Small amounts of the prized substance were rumoured to be found inside vintage Singer sewing machines.

Police began investigating the hoax after these very ordinary household objects started changing hands for tens of thousands of dollars.

Red mercury scare

Rumors about the substance have also been given traction by global geopolitics. In the late 1980s, as communist regimes collapsed across Eastern Europe, there was uncertainty as to what was happening to their stockpiles of nuclear material.

At the time, Mark Hibbs was a journalist investigating alarming rumors that a previously unknown nuclear material, created in Soviet laboratories, was being offered for sale by shady individuals. Its name? Red mercury, of course.

Mark, now a senior fellow at the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, a US foreign policy think tank, says that the atmosphere of uncertainty at the time contributed to the whispers.

“The Soviet Union was a place that over a number of decades secretly accumulated nuclear inventories across a massive territory,” he says. “It wasn’t clear to us at the time that all those materials – as the Soviet Union began to disintegrate – would remain under lock and key.”

This version of the red mercury story was different from the one about the all-healing elixir buried with the pharaohs. Soviet red mercury was said to be destructive, capable of causing a tremendous nuclear explosion with quantities no larger than a baseball.

The nightmare scenario was that this substance might find its way onto the weapons black market and end up in the hands of terrorists or rogue states.

However, Mark Hibbs says that when Western governments investigated, they concluded that the doomsday material didn’t exist.

So how had the rumors started? Mark says Russian scientists told him that red mercury was actually a nickname for a known nuclear isotope. But when he asked the Russian and US governments, neither would confirm nor deny if that story was true.

And a rival theory emerged – that the US government had surreptitiously spread red mercury rumors as a way to entrap terrorists. But again, there was no hard proof or official confirmation.

Not quite red-handed

Since then, however, the rumors have featured in several terror cases. In 2015, the New York Times reported that members of the so-called Islamic State group had been arrested in Turkey for attempting to buy red mercury.

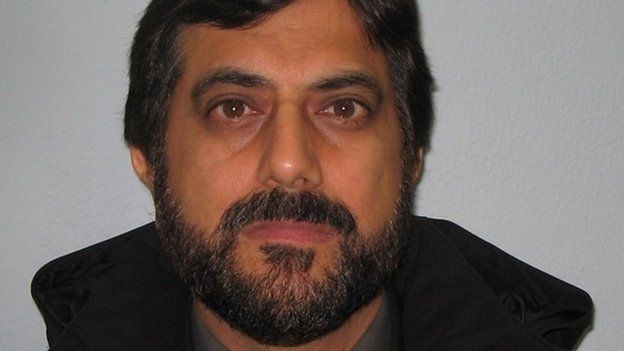

And in Britain in 2004, three men were arrested and charged with terrorist offenses, again after allegedly trying to buy the substance.

Their trial heard how an undercover reporter, Mazher Mahmood, better known as the News of the World’s “fake sheik”, claimed to be hawking nearly a kilogram of red mercury.

The prosecutor, Mark Ellison, told the jury: “The Crown’s position is that whether red mercury does or does not exist is irrelevant.”

Prosecutors said the three men were looking for ingredients for a “dirty bomb” which could have devastated London. But one of the defendants said he was interested in the liquid to wash discoloured money. All three were acquitted of all charges.

Despite high-profile cases and debunks, the many fantasies around red mercury have remained stubbornly impervious to reality. And now those YouTube videos and online adverts have spread the hoax to new generations.

YouTube told us that the bizarre videos featuring red globules don’t necessarily violate its policies, however, it would evaluate on a case-by-case basis whether such videos were suitable for its advertising program.

Facebook and Twitter said they took a tough stance against fraudulent activity, and they took down the red mercury adverts we pointed out to them.

The real red mercury

Finally, there is a red-colored mercury-containing ore that does actually exist. Mercury sulphide, to give it its proper name, is a comparatively mundane substance. It’s also known as cinnabar and although it is very useful for decorating pottery, it cures nothing – and could actually be harmful. Not because it’s highly explosive, mind you, but rather because plain old mercury is hazardous to human health.

However, if you are still tempted to go online to purchase red mercury for a miracle cure, then can we perhaps also interest you in buying some magic beans?